RISE DIGITAL LEARNING SERIES

Identity

Identity can be defined as who someone is and the qualities and beliefs that make a particular person or group different from others. Therefore, when we think about our identity, we are reflecting on how we are made up and how that is related to our sense of self.

The recent protests against police brutality and racism have revealed a lot about our nation's identity. It has revealed that our country's identity is a fragmented one, made up of very disparate parts. Some parts of us still judge people on the basis of their race, gender and sexual orientation, while others are willing to act, be allies and advocate for equity. Our identities are indeed complex and this topic explores that complexity. While we see ourselves in one way, we are simultaneously being labelled and categorized by others. Identity therefore becomes an integration of the ways we understand ourselves, and the ways we think others see us. At the same time, there are parts of ourselves we love, and parts that, if we are being honest, we try to improve daily. Thinking and talking about identity is an important place to begin discussions around race and diversity because it establishes who we are, our values, our beliefs and the ways in which we are both similar and different from one another.

"We define our identity always in dialogue with, sometimes in struggle against, the things others want to see in us." — Charles Taylor

RISE Perspectives

This week, as we think about identity and the role it plays in racism and inequality, we recognize that how we are seen by others can often be in conflict with the ways we view ourselves. It's that duality that gives some power and privilege in society and limits other people. In light of that, we want to share this perspective piece written in May 2020 by Dr. Andrew Mac Intosh, who shares a little about his identity and how it has been impacted by the events surrounding Armaud Arbery's death.

A Tale of Two Months

By Dr. Andrew Mac Intosh

It's been two months since my company has been working from home. That fact dawned on me recently for a couple of reasons.

The first is that being at home has allowed me to spend more time with my kids and for us to do things together, like exercise. We haven't done much, but a few push-ups here and there is refreshing to someone feeling their athleticism slipping away. The second reason was Ahmaud Arbery. A news headline reminded me that it had been two months since he was shot and killed.

The reason his death has stuck with me, though, has less to do with the outcry for justice. It is less that he was in the prime of his life and essentially hunted, or that I have two sons of my own, and I pray something this terrible would never happen to them. This particular death has stuck with me because two months prior I had half-jokingly suggested to my mother that this could happen to me.

I remember telling her the weather in Michigan, where I live, was warming up, and I wanted to begin running again but wouldn't because of COVID-19. She said I should just wear a mask and go early when no one is around to maintain social distancing. I then said: "You want me, a black man, to put on a mask, and run, in Michigan?" She laughed and so did I. Like I said, it was half-joking.

But it's the serious part of that conversation with my mother that led me to doing push-ups instead of going out for a run.

Ahmaud Arbery

One of the saddest aspects of Ahmaud's death for me is the fact that according to all the publicly available evidence, he was killed doing what so many of us are doing in this time of social distancing - exercising.

One study estimates rates of exercise are up by as much as 88 percent since the start of the pandemic. Running rates are up by as much as 117 percent. While so many Americans are using exercise as a mechanism to help cope with the stress and social turmoil brought about by this pandemic and its accompanying economic challenges, exercise is responsible for this young man's death.

His death reaffirms the fact that being able to safely and comfortably run, walk or jog outside isn't a privilege universally shared. I know I'm not alone when I thought, "that could have been me."

If you criticize me for focusing on this one aspect of this tragedy and not some of the others, I would understand. I agree that there are many frustrating aspects to this case.

Ahmaud was killed because, like so many other people of color, he was assumed to be guilty and dangerous simply because he was black and running. This has been true of many other killings, but the fact that Ahmaud was, of all things, exercising strikes a chord for me that is unprecedented.

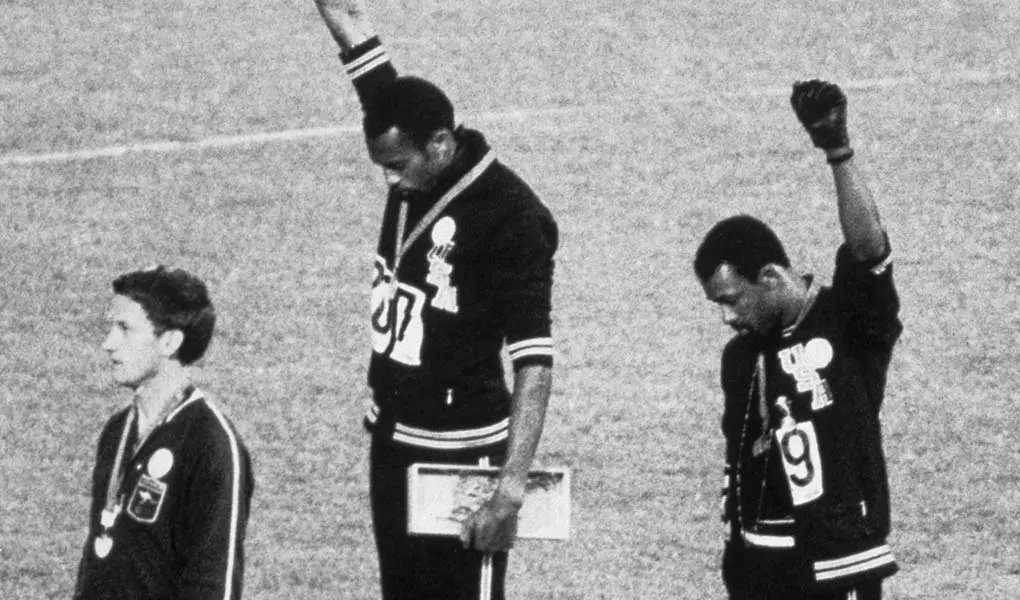

Sport is one of the most quintessential of all American pastimes. The American Academy of Pediatrics has estimated that 60 million youth participate in organized sports annually. Sports contributes $60 billion to the economy each year and athletes, at all levels of sport, are household names in their community. That this former high school athlete could go out to exercise like so many Americans and be killed because he ran past the wrong men, in the wrong neighborhood, simply does not seem right.

Which American heading out for their morning run, as so many of us are doing during this pandemic, think we might be mistaken for a burglar? The reality is, it crosses the minds of many people of color. It's this reality that led me to doing push-ups instead of running.

In my professional life, I lead the creation of curriculum at RISE, a nonprofit that educates and empowers the sports community to eliminate racial discrimination, improve race relations and champion social justice. Our work is based on the premise that sport is a platform that brings people together and provides an opportunity to address issues of racism, bias and inequity. Sport allows people to work together towards a common goal or come together to root on the same cause in spite of the obvious or deeper differences that might exist among them. Regardless of age, race, nationality or ideological differences, sport exemplifies that teams and organizations can be successful even where differences exist. Using sport to bring people together, we can teach the skills required for people to be culturally competent and spark much needed conversation around issues of race and injustice.

It is for this reason that we need to stop and consider seriously what took place in Brunswick, Georgia. It's the circumstances of this case that fuel discussions of fear, privilege, injustice and racism for many people of color today.

The facts of this case lead to awkward jokes between mothers and sons at odd hours of the morning. Killings like these, and this one in particular, suggest that as a black man in America, I can be doing what I have every right to do and still get killed.

Just months ago, while many of us were working out in our basements, gyms or through the streets of our neighborhoods, a young black man was shot and killed for no explicable reason.

Andrew Mac Intosh, Ph.D. holds degrees in Kinesiology, Applied Psychology and Sociology. As Vice President of Curriculum at RISE, he is responsible for the design, delivery and evaluation of RISE's leadership and cultural competency curriculum, which is administered to professional, collegiate and school-aged athletes, coaches and administrators throughout the country.

How we see ourselves and how others see us make up a significant part of our identity.

Complete this activity to learn more about your identity.

Go to ActivityHow does your identity shape you as a leader?

We asked a diverse group of leaders to talk about different aspects of their identity, and how it defines their ability to foster inclusion and help create a more equitable society. Click on each person to see what they had to say.

College Athletes Talk Identity

Watch student-athletes from across the country discuss identity.

- What does your identity mean to you?

- Does how others see you affect how you see yourself?

- Is being a student-athlete formative in identity?

Learn More to Do More

Connect with friends and family and check out our "Identity Circles" activity. Explore labels central to our identities and discover just how fluid our identities can be, while examining the value of diversity.

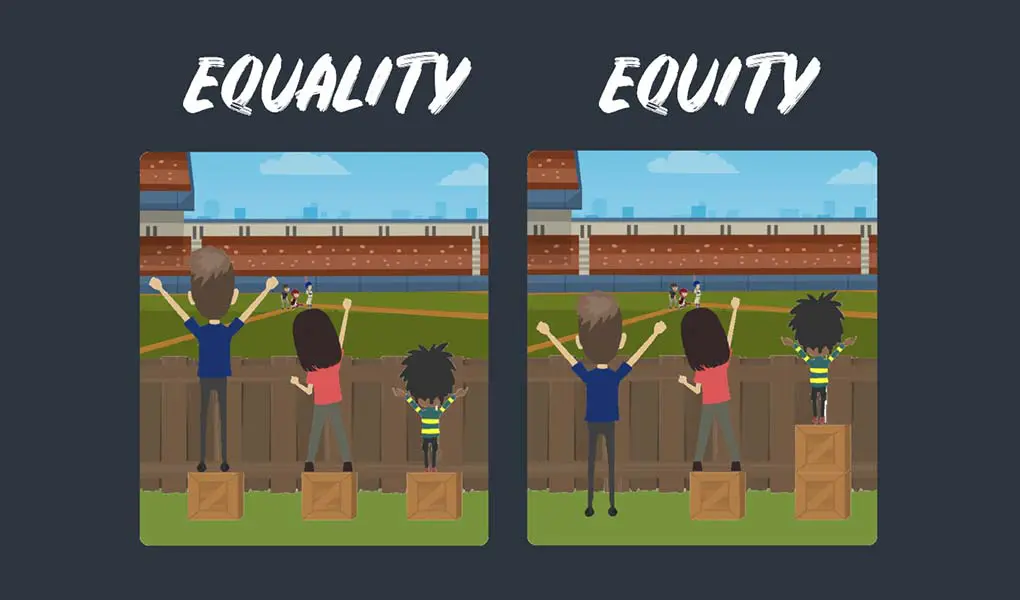

In Course 1, we defined identity as "who someone is and the qualities and beliefs that make a person or group of people different from others." While we see ourselves in one way, we are simultaneously being labeled and categorized by others. Racism, prejudice and other forms of discrimination are based on these categorizations. We make judgments about people's intelligence, wealth, attractiveness, character and even their humanity based on the color of their skin and other demographic characteristics. Historically, this has been used to give some groups power and deny others. The right to vote is perhaps the greatest power we possess in our democracy, and people have historically (and currently) been denied that right because of their identities.

"I used to have my hair short, I now have it very long and the world began to treat me differently. … It made me realize that I'd changed what I thought was a trivial aspect of who I was but it profoundly made a difference in the way the world perceived me." — Malcolm Gladwell

RISE Perspectives

Sports have united against racism. We need to fight anti-Semitism too.

By Ian Cutler

Throughout my time at RISE, I've learned more about the Black experience in this country. In particular, the experiences of Black parents and the conversations they're forced to have with their children about how many might perceive them as "a threat."

Having become a father a few months ago, it's a horrifying prospect to explain to your child that they're naturally seen as suspicious and to ask them to always be on alert, stay out of certain neighborhoods or present themselves in a way that's counter to who they truly are, out of necessity – to stay alive.

Being Jewish, I've always empathized with people of color in this country, knowing the history of my family and Jewish people around the world. But now as a father, I think even more about Ahmaud Arbery's, Trayvon Martin's or Michael Brown's parents, and the conversations they must have had with their sons who still fell victim to racism's most tragic result.

I won't have to have those conversations with my son and that alone personifies the privilege that white and white-passing Americans, like myself, possess.

It's estimated that around 12-15 percent of Jewish Americans are Jews of Color, but for many Jews, we can pass as white, and for the most part are afforded the benefits of the privileges our skin color provides. But being Jewish is also not the same as being white in this country. We too have a minority experience of being "othered" and demeaned and face the threat of violence because of who we are. I was reminded of that again by recent actions of the sports community.

It began with Philadelphia Eagles receiver DeSean Jackson's anti-Semitic Instagram post attempting to share a message about Black empowerment. On July 7, Jackson posted the words of the widely condemned anti-Semitic and homophobic leader of the Nation of Islam, Louis Farrakhan, and falsely attributed a quote to Adolf Hitler: "White Jews will blackmail America. [They] will extort America, their plan for world domination won't work if the Negroes know who they were."

Jackson later apologized for his post, admitted his ignorance and pledged to do more to learn about the Jewish experience and the dangers of the stereotypes he was promoting, much like the way Drew Brees committed to learn more about the Black experience after his recent comments about protests during the national anthem.

While hurt, I was encouraged by Jackson's approach and hoped this incident would create an opportunity for the sports and social justice movement to include and learn more about the Jewish experience and the bonds we share with other marginalized groups in this country.

Many are unaware of the persecution, exile, torture and genocide that Jewish people have endured globally for centuries. Take the 850,000 Jews expelled from Arab countries and Iran throughout the 20th Century or the pogroms of Jews in Eastern Europe leading up to the Holocaust. Jackson is not alone in perhaps not being fully aware of who Hitler was, the 6 million Jews Hitler's Nazis murdered, the millions more he imprisoned and tortured or the tactics Hitler and others historically have used to turn entire societies against the Jewish people – among them, falsely accusing Jews of controlling banks and seeking "world domination."

Anti-Semitism has been a problem here, too. My grandparents, fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe, were initially denied entry into the United States in the 1920s because of immigration quotas restricting the number of Jews allowed to emigrate here. The same people who didn't allow African Americans to join their country clubs, attend their schools or buy a house in their neighborhoods took measures to exclude Jewish people from living, studying or playing with them too. Those practices are still being fought today. During the infamous 2017 "Unite the Right Rally" in Charlottesville, Virginia, white supremacists marched with torches chanting, "Jews will not replace us." Mass shootings at synagogues in Pittsburgh and Southern California occurred as recently as 2018 and 2019, respectively. These are just some examples.

African Americans and Jewish Americans are therefore on the same side as marginalized groups in this country and this world. While we may not have the same experiences or face identical plights, we are in the same fight.

But since Jackson's post, an alarming number of athletes and cultural icons, some revered for their social justice leadership, have shared hateful and ignorant sentiments about the Jewish people. Instead of a teaching moment that sparked a more inclusive movement against all bigotry and discrimination, what developed was a national debate about the validity of Jewish stereotypes and a wedge between peoples.

NBA legend Stephen Jackson's voice was instrumental in helping ignite the necessary national reckoning on racism following the murder of his close friend George Floyd.

But Jackson defended and later doubled down on the anti-Semitic tropes and stereotypes that DeSean Jackson had posted, calling them "truth" even after DeSean's apology. Subsequently, he evoked the Rothschild Family and advanced conspiracy theories about Jews controlling all banks and thus a society's politics, economy and social structures – common themes of Nazi propaganda used as "evidence" to persecute Jews.

The revelation that Nick Cannon had perpetuated the same stereotypes against Jews a year earlier and was now fired by Viacom because of it inspired Big3 founder Ice Cube and NBA legend Dwayne Wade to come to his defense. Wade, who I've always admired as a champion for progressive social causes, apologized for jumping to Cannon's defense without realizing the nature of what he had said and pledged to learn more about such stereotypes, while Cannon himself has already taken steps to do the same and help bridge divides among Jewish and Black communities. But Ice Cube, who also recently shared anti-Semitic social media posts, went after leaders like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar for calling out Cannon's and Jackson's anti-Semitism, saying such condemnation was a betrayal of the Black community.

Malcolm Jenkins, a co-founder of the Players Coalition, called DeSean Jackson's comments wrong, but disappointingly dismissed the arguments and outrage over his anti-Semitic statements as "a distraction" and added that, "Jewish people aren't our problem, and we aren't their problem."

Soon after Jackson's post, hateful hashtags like #Jews and #JewishPrivilege were trending on social media. Then on Aug. 6, Oakland Athletics bench coach Ryan Christenson gave players a Nazi salute as the team celebrated a win. He was quickly corrected by players on the field and later apologized for making the "racist and horrible salute," but even in his apology and the team's statement that followed there was no acknowledgement of the anti-Semitic charge behind that gesture and no attempt to enact discipline or commit to learning more.

What this all showed me was a lack of understanding and empathy within the sports community for Jewish suffering and our history of allyship in the fight for racial equity. For people I admire like Jenkins to not realize the connection between our peoples, or for Stephen Jackson to single out Jews as "not doing enough" to fight racism honestly caused me to question my place in the larger social justice movement. Of course we can all do more to advance racial justice, and it's true that Jews of Color have had to push for full acceptance within the larger Jewish community, but all of these statements made me feel vilified and scapegoated like my ancestors before me.

In addition to Abdul-Jabbar, there have been significant leaders and voices like Jemele Hill and Charles Barkley who have spoken out about the need for more outrage over anti-Semitism and the unity that African Americans and Jewish Americans must maintain to combat bigotry. But as a Jewish person working for an organization that uses sports to combat racism, I was especially hurt by these events and the way this issue has ultimately died down without much action or acknowledgement from the larger sports community.

Working for RISE, I am proud to continue a legacy of Jewish Americans fighting racism in our country. Speaking at the March on Washington in 1963, Rabbi Joachim Prinz said Jews and African Americans were natural allies because of our shared history of oppression and that it is incumbent on all of us to speak out and act against racism, saying, "The most urgent, the most disgraceful, the most shameful and the most tragic problem is silence." The famed Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel echoed this message of unity between our two communities and joined Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. on the famous march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965. Jewish Americans played an essential role in the work of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) and Freedom Riders fighting segregation in the South. The Ku Klux Klan murdered Jewish Americans Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner for trying to register African Americans to vote in Mississippi as part of the Freedom Summer in 1964, just before the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Jewish community in which I was raised instilled me with values that call on us to fight for equality. I know that my skin color affords me privileges and opportunities that Black and Brown Americans do not have, and that it is my responsibility to use that privilege to create a more inclusive and equitable society.

It is also my responsibility to speak with my son about racism. It is my job to help him develop empathy for those who face racial bias, and to expose him to the unfortunate realities people of color must deal with daily so he is best equipped to help create change. It is my job to inspire him to seek a diverse group of friends and to teach him to be an advocate for racial justice.

But in that same conversation, I too will have to explain that he also might be forced to hide who he is to avoid bullying, discrimination or violence. I'll have to explain people in this country will be raised to believe that we, as Jews, are greedy, conniving and determined to control the world and oppress others, and that some of the athletes and movie stars who define our American culture, who he and his friends will look up to, are the same people who believe we are the main reason for their suffering and the endurance of systemic racism. I'll have to tell him why our synagogue has armed security and metal detectors, and why I might wait until we approach the synagogue doors to put on my kippah and remove it as soon as we leave services.

The most recent data from the Anti-Defamation League reported record acts of violence against Jews. Anti-Semitism is unfortunately one of the few things that lives across political parties. It exists on all sides of the aisle, in all cultures.

In this country, anti-Semitism is not entrenched in our social structures the way racism is a systemic issue. Still, the ultimate danger of anti-Semitic stereotypes is the way governments and individuals have historically used them to kill and persecute Jews. We cannot allow such tropes to carry any weight while thinking that what has happened to Jews throughout the world can't happen again.

My aim is not to debate the severity of different minority experiences or argue over who has it worse. It is instead to call on all of us to learn from and empathize with each other and realize that we are in this together.

It is to live by the Jewish principle of "Tikun Olam," to use our time on earth to make life better for everyone and create a more equitable and harmonious society for all.

The core message of Black Lives Matter is critically important. The fight against anti-Semitism does not distract from it. They can and should go hand in hand.

My hope is that more sports leaders, who have been so instrumental in advancing the conversation around racial injustice, will also take time to learn and speak out against the dangers of anti-Semitism.

True equity cannot be achieved by denigrating one group to lift up another. We all must be better allies for each other.

Ian Cutler is RISE's Sr. Director, Communications.

At the beginning of our country's democracy, only 6 percent of citizens were allowed to vote - white men that owned land.

Since then, some of our nation's most defining moments have improved the democratic process to include people of color and women. It is clear to see that identity and voting rights are intersected.

This is why we need to understand our history, the progress we've made and the distance we still have to go.

To scroll through the Road to Progress timeline, please use the arrow keys on your keyboard.

The right to vote is perhaps the greatest power we possess in our democracy, and people have historically (and currently) been denied that right because of their identities.

At RISE, we believe it is imperative for everyone's voice to be heard and our work revolves around making that a reality.

Start Now

Our

Partners

Stay

In Touch

Follow us on social media.